Pediatric ophthalmologists and developmental optometrists each see skewed populations when it comes to children with vision based learning problems. Parents who, for whatever reasons, elect not to pursue optometric remediation through low power prescriptive lenses, prisms, or vision therapy may seek reassurance that nothing’s wrong by consulting with an eye surgeon. Conversely children with legitimate vision problems whose parents are assured by eye surgeons that there is nothing to be concerned about may seek clarity from a developmental optometrist because they sense that their child is not crying wolf.

Pediatric ophthalmologists and developmental optometrists each see skewed populations when it comes to children with vision based learning problems. Parents who, for whatever reasons, elect not to pursue optometric remediation through low power prescriptive lenses, prisms, or vision therapy may seek reassurance that nothing’s wrong by consulting with an eye surgeon. Conversely children with legitimate vision problems whose parents are assured by eye surgeons that there is nothing to be concerned about may seek clarity from a developmental optometrist because they sense that their child is not crying wolf.

In my 37 years of practice I have encountered hundreds if not thousands of instances where a parent came to me with their child, convinced that something is legitimately wrong, after having been assured by the pediatric ophthalmologist that everything is fine. Parents generally know their children best and particularly when a child who is not a complainer complains about her vision, there is usually a logical explanation. Alexandra is the most recent example, and because her case and documentation is fresh in my mind I’ll share this classic instance of the ball being dropped.

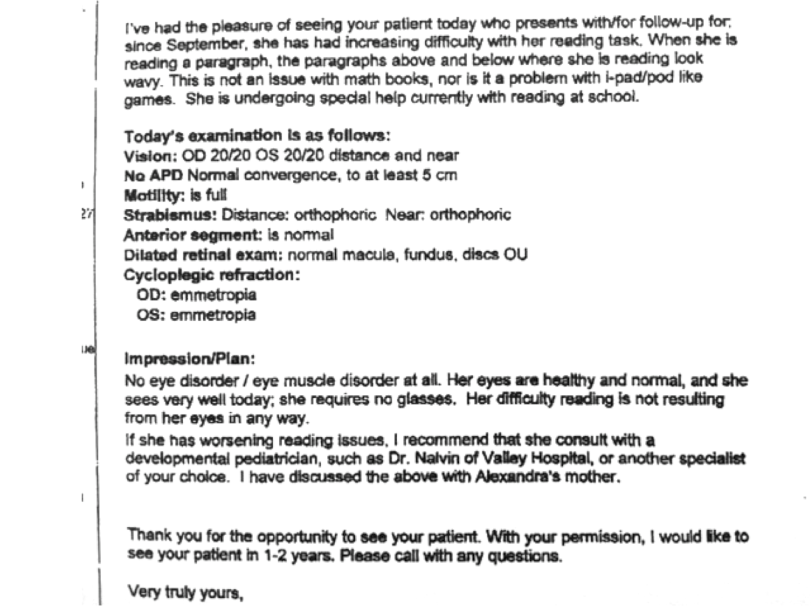

About a year and a half ago, Alexandra – who is now 11 years old – began to experience difficulty with reading. Not that it was ever easy for her, but she was now aware of the instability of print when trying to read. Her pediatrician referred Alexandra to a local pediatric ophthalmologist, who wrote the letter that you see here. The doctor found that Alexandra’s eyes were healthy, that she has normal visual acuity, no refractive error, no restriction in eye movements, no strabismus, and that convergence was intact. Despite the fact that she noted Alexandra had difficulty only with reading text, and not with math computation or i-Pad games, she concluded: “Her difficulty with reading is not resulting from her eyes in any way”. This was back in February 2013, and despite the fact that Alexandra was already receiving special help in reading in school, which did not alleviate her symptoms in any way, the pediatric ophthalmologist could only suggest that if the reading issues worsened a consult with a developmental pediatrician would be in order.

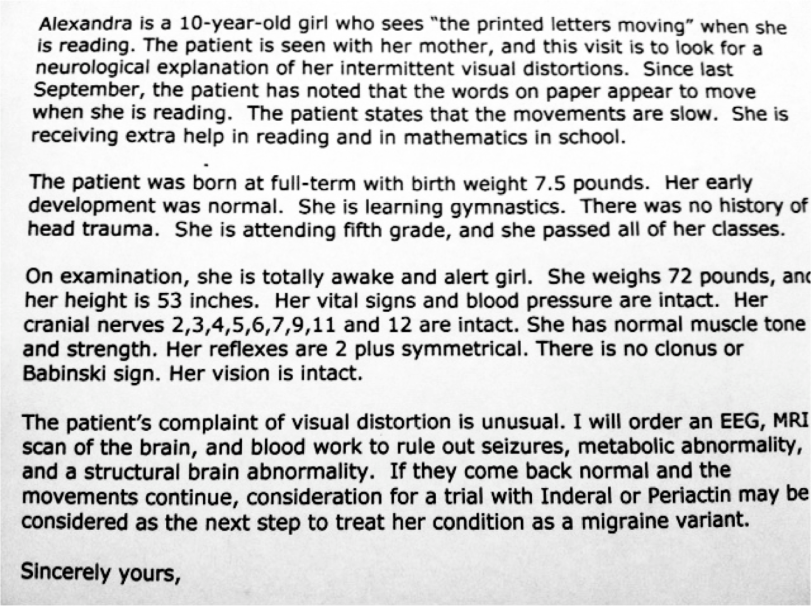

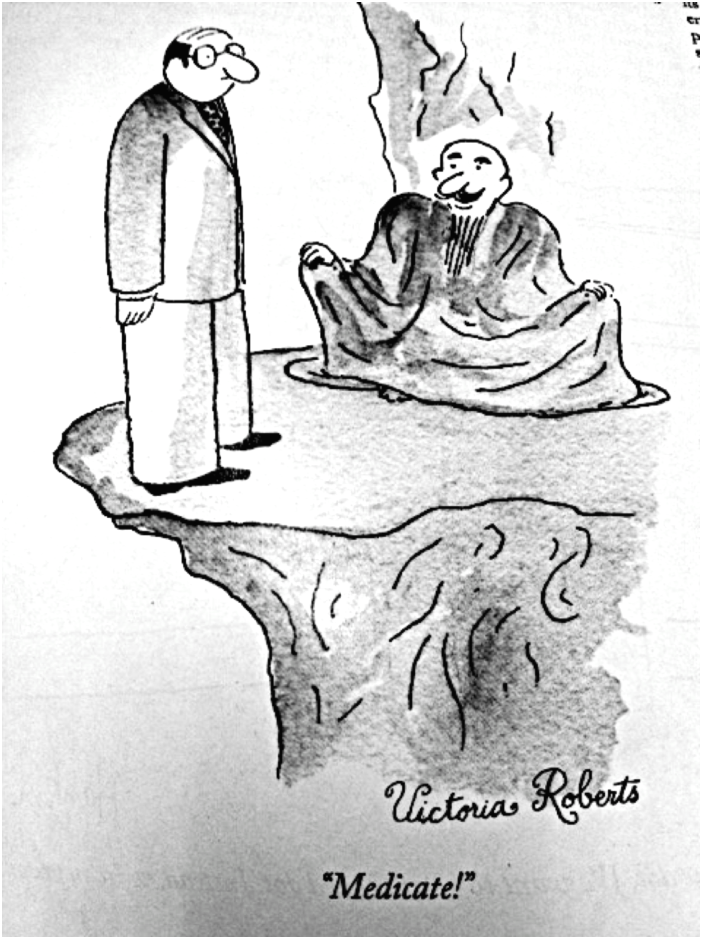

A month later the instabilities of print that Alexandra experienced were not improving, and she was becoming discouraged. Although she was receiving extra help in math and reading, her basic ability in computation was excellent as long as it did not involve word problems. As soon as print was laid out on a page like reading, the shimmering predominated and it was tough to maintain concentration yet alone comprehend what she was reading without working extremely hard at it. And even so, it was a struggle. Distressed at having no answers, Alexandra’s mother took her to a pediatric neurologist who found her complaints of visual distortion to be unusual. As indicated in her letter, she ordered an EEG, MRI, and blood work to rule out medical abnormalities. The plan, if results were normal and the instability of print continued, was to treat Alexandra as having a migraine variant, and therefore start her on drug trials.

While I have no fundamental opposition to a trial of medication when appropriate, you may have already sensed the flaw here that both doctors overlooked. One clue is that Alexandra’s visual instabilities did not exist when print was wider spaced, as with non-word math problems. Asking Alexandra if print size made a significant difference in her perception – which it does – could have easily, confirmed this. The other clue is that Alexandra experience no difficulties with i-Pad games, computers, TV, movies, and so forth – activities which should be more of a visual trigger to migraines that reading a page in a chapter book.

Sure enough, all tests including blood workup, EEG, and MRI were negative. Alexandra’s mom intuitively grasped that medication made no sense, so she decided to consult with another ophthalmologist. This time the ophthalmologist explained that Alexandra did have convergence insufficiency, and that she might benefit from vision therapy, but that there are two types of therapy and only one works. She asked him to write her a letter because she didn’t understand what he expected her to do. This was back in May, and she’s still waiting for the letter.

At her wit’s end, Alexandra’s mother searched the Internet to see if she could find more guidance and a specific course of action, ultimately bringing her to my office last week for an evaluation. For many years when people asked me what I did for a living, I’d give them either a technical description and watch their eyes glaze over, or a very simple descriptor such as working with patients who have visual problems that can’t be fully corrected with standard eyeglasses or medications. It may be even simpler, and more to the point if my answer to the question is that my job is to gather dropped balls.

Dr. Press, I receive your posts via email and look forward to them. Thank you for your honesty and willingness to “take this issue on.” I am an Ot who work closely with students who struggle with handwriting – and hence, with educational success. I am fortunate to have an excellent developmental optometrist “on my side” here on Cape Cod to assess and recommend vision treatment to my clients….when their parents understand the importance of vision assessments and therapy. Unfortunately, the recommendations of their pediatricians and ophthalmologists often cause them to decide that vision assessments are the ideas of “quacks” and that none of that works. I will continue, however, to spread the word…as I have seen them work. Thanks for sharing your great insight in your posts.

Thank you for being a regular reader, Katherine, and for the kind words. As we know, the American Academy of Pediatrics as recently as last year was telling parents that Sensory Processing Disorder was a contrived diagnosis by OTs who think that everyone needs therapy (see http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAP-Recommends-Careful-Approach-to-Using-Sensory-Based-Therapies.aspx). Although many parents still accept what their pediatricians and ophthalmologists tell them at face value, there are increasing numbers of parents who look beyond superficial assessments of vision. It is precisely because of professionals such as you that this is occurring, and thanks for your good work.

Dr. Press, Thank you for your support of my work. It was the dedication of a behavioral optometrist in Albany, NY, Dr. Robert Fox, that set me upon this path, as he and I worked together with patients who had experienced a stroke. He was kind enough to teach me, guide me and to invite me to the COVD convention in NYC that year. The rest is history. I enjoy your blogs and will continue to share them with my readers and clients.

Keep on screaming from the mountain tops! Unfortunately, this is all too common. In testing, we are taught to not use the words always and never. Perhaps someone should teach the peds ophthalmologist that rule!

So all of the testing cost about $5000 or so with no idea of a solution. I wonder what else that money could have gone to pay for? 🙂

Love the story!

Marc

It’s an interesting case and I think it is normal not only in USA, but also in Italy (from where I write). Only one thing: if the child had a SPECIFIC reading problem, why parents had no contacted specific reading specialist such as neuro-psychologist or developmental psychologist?

I know that in different countries there are different specialist that work on the same problem, but based on these data I think that the primary professional to contact is neuropsychologist. Clearly the n.psy. to exclude other related condition needs to have a opthalmology AND optometrist exam documentation.

Clearly not in all cases optometrist were contacted…

In our system,Alessio, this child has already been evaluated by her school system and is receiving remedial instruction in reading.

Precisely, Marc. And these MDs set themselves up as patient “advocates” so that the “medical home” can protect them from unnecessary tests from other providers. Quite a double standard, isn’t it.

This is a great and so very true. My son’s life would be dramatically different if it wasn’t for vision therapy. He now plays travel baseball, pitches and is a great hitter. He is getting A’s in school. Many doctor’s told me vision therapy does not work. Well my son is living proof that it does. I thank god every day that he is able to live a normal, healthy and happy life. Thank you Dr. Press!!

Thanks so much for lending your voice to this crucial issue, Sharon. Social networking has been a tremendous boon to parents learning from one another that this nonsense that “vision therapy doesn’t work” is an insecurity on the part of pediatriricans and ophthalmologists who can’t bear to admit that optometric vision therapy has legitimacy. By continually bashing VT they deflect attention from their own practices, many of which for years has been based on art and much as science, and “off-label” consensus rather than prospective scientific research. Time to hold them accountable for the double standard.