The original “The Country of the Blind” was a short story by H.G. Wells published in The Strand magazine in 1904. It is the source of the famous quote: “In the country of the blind, the one eyed man is king”.

It’s a line cited by Andrew Leland in his new book The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the end of Sight.

Andrew has retinitis pigmentosa, and on page 27, reveals he’s luckier than most because he has a financial cushion to soften his fall into blindness. That is thanks to the nice chunk of change left to him by his grandfather, who grew up in a crowded apartment in Washington Heights. His name was Marvin Neil Simon, and he dropped the “Marvin” from his name as he became a famous playwright. The writing genes are in Andew’s family, as his mother Ellen became a playwright in her own right.

The book is very well done, and from a vantage point that you don’t often see. Andrew writes that humans are so fundamentally visual in their understanding and experience, and that vision holds such a privileged place at the top of the hierarchy of the senses, that blindness requires its own domain.

The visual loss in RP is so gradual, and leaves central vision intact well enough and long enough, that in many instances the individual is left with what Andrew describes as paradoxical double vision. By that he means the simultaneity of seeing through sighted eyes, but as peripheral vision shrinks through blind eyes as well. He makes the powerful statement that he feels as stymied by the vision he still has as by the vision that he has lost.

Leland notes that the Ancient Greeks had one word for totally blind people (the 15% who have no light perception) tuphlos, and a different one for those who have some degree of vision loss, ambluôpia which means “dull-sightedness”. He described having felt like an impostor, constantly vacillating between feeling too sighted to be blind, and too blind to be sighted. There is a hierarchy of sight among the legally blind.

Attending the annual meeting of the National Federation of the Blind, Andrew meets a journalist Will Butler who captures this paradox well by writing that even the phrase “going blind” can be problematic: “Going blind has baked into it all the loneliness and isolation that we associate with blindness. A much more accurate way to describe it is becoming blind; blindness is much more an arrival than a departure.”

A particular treat in Andrew’s writing is his first visit to Mass Eye and Ear, which started like any garden-variety optometrist’s appointment using the Snellen chart. He writes: “As I made my way farther down the rows the letters began folding themselves into vibrating, illegible starlike clusters of silver pixels … I wish the nurse could just scan my eyes with a Star Trek tricorder and learn everything she needed to know …

… But vision is a powerfully subjective substance, one that is still most accurately measured by the patient’s own report. Doctors appraise all the senses this way with odd quizzes designed to standardize an elusive, highly interpretable impression … Raised in a culture that worships the authority of doctors, I find it difficult to trust entirely in my own report. Reading the chart and answering their questions, I felt like an unreliable narrator of what should be indisputable: my own direct observations.”

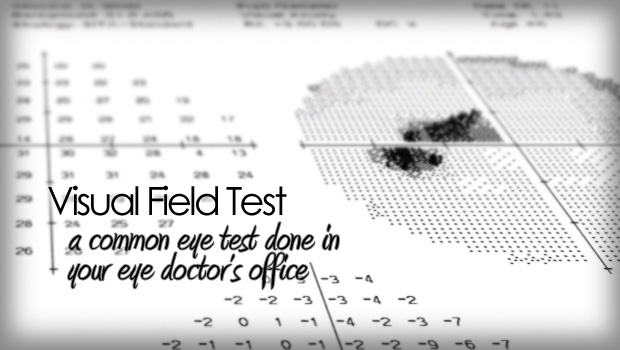

Andew proceeds to describe his visual field test. Peering into a the tiny amphitheater with a dull yellow light shining in its center, “The nurse haded me a game-show-style buzzer, which she told me to press whenever I saw a pinprick of wobbly light moving from the periphery of the amphitheater toward the light at its center. For most people, this test is as routine as the eye chart, a little medical carnival game. But as I waited to see the wobbly lights emerge from my dead periphery, impotently clutching the buzzer through the long silence, certain that the light would have been visible to someone with a normal visual field many minutes ago my anxiety grew. Finally, a light appeared directly in front of me, and I gave the buzzer a squeeze, the worst contestant in the history of Jeopardy! …

… The doctor showed me the results of my failed appearance on optical Jeopardy! – the visual field test. This was the schematic that had once reminded me of ice cubes, the one that described how much vision I’d lost: the roughly symmetrical pairs of diagrams, one for each of my eyes, with small, wobbly ovals at their centers (the twin portholes of my residual central vision), flanked by two slender, curved shapes (representing my periphery). The doctor said that those slender shapes were the bits of vision I was using to get around. There’s a clinical term for this: ambulatory vision.”

Andrew proceeds to explain that the U.S. has a legal definition of blindness that has only been around since the 1930s, and that it is predicated on a loss of eyesight and/or a constriction in peripheral vision. He explains, somewhat frighteningly, that some individuals don’t want to be classified as legally blind because that would require them to stop driving, or they still have careers in fields that require vision.

As you read this, think of drivers on the road who make poor judgments. Surely many of them are impulsive or distracted drivers. But a subset of them may be individuals who would have their license restricted or rescinded based on poor visual acuity or visual field constriction of states bothered to periodically re-test visual requirements for licensure. There is so much about vision and driving that we take for granted (see here for example).

The other thing that struck me is how hard we work to get the point across that vision is more than 20/20 eyesight, but how inadequately we do that. Visual fields are just another example of the tortured semantic relationship between sight and vision. When we have poor peripheral vision, we refer to that by saying that we don’t see well in the periphery. That’s a really poor choice of term if eyesight is linked to visual acuity.

This battle we have fought to differentiate eyesight from vision is a perennially losing one because we, ourselves, conflate the terms. “Well Mrs. Jones, losing peripheral vision means you don’t see things as well to the side when you’re looking straight ahead”. The problem of course is that we don’t have a verb for vision. Any aspect of vision that involves movement is described as some variant of seeing.

But enough about our problems confounded by semantics. I’ve blogged before about books I’ve read regarding which I’ve said: “Don’t run out and buy it”. But this one I’m going to recommend that you buy, and be enlightened as well as entertained as you read it cover-to-cover. Grandpa Neil would have been proud.